Reviewer: Wouter van Dijk

Reviewer: Wouter van Dijk

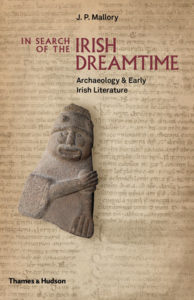

In Search of the Irish Dreamtime. Archaeology and Early Irish Literature, J.P. Mallory

Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 2016

ISBN: 978-0-500-05184-9

Hardcover with dust jacket, illustrations in colour and black-and-white, figures, maps, notes, bibliography and index

320 pages

£18,95 / € 23,00

Investigating the historicity of ancient Irish tales

In a way In Search of the Irish Dreamtime can be seen as a companion to The Origins of the Irish (2013) by the same author. In Origins the native Irish account of their own origins as a series of invasions is briefly dealt with. This ‘Oldest Irish Tradition’ consists of an interwoven web of semi-historical and mythological tales and in this book, In Search of the Irish Dreamtime, J.P. Mallory aims to disentangle the knot of fact and fiction formed by these tales. Frequently researchers bring up these tales from the Mythological Cycle and, especially, the Ulster Cycle as if they could provide a ‘window’ on the Iron Age or in instances even the Bronze Age because of descriptions of human behaviour or materials. Mallory’s purpose is to provide us with an overview of what exact archaeological evidence exists for these claims. In other words, can there really be found prehistoric echoes in early Irish literature or are these stories formed by the Early Medieval society in which they were penned down, in addition to some creative writing from the side of the monks who took care of the tales?

First Mallory gives a brief summary of the tales under scrutiny, which are those that are part of both the Mythological and Ulster Cycles. He seeks to compare elements of the Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley), with the Iliad of Homer in order to discern possible historical and archaeological elements out of the fable of which the tales are composed. The Táin Bó Cúailnge is the most important of the series of scéla, as the tales are called in Irish, that are making the Ulster Cycle, hence the choice for it as main focal point for the research. In order to separate fact and fiction Mallory looks at the origin of the metric in the tale, the use of verse and prose and the material culture that comes forward through the descriptions in the scéla.

In order to learn to what extent evidence of prehistoric culture survived in the mythological tales of the Táin, the author uses a variety of literary ‘excavation’ techniques. The first of these is etymology, which can be used to trace the linguistical origins of a word. A second tool is the way material culture is described. The description of weaponry for example, can tell a lot about the period in question. A third way is the use of the context in dating elements of the tales, when a great silver treasure is mentioned for example, it seems like an Iron Age dating is out of the question, since silver only became frequently used in Ireland after the Viking incursions from c. 800 AD onwards.

With these tools of excavation Mallory systematically analyses all aspects of the natural and material world in the Táin Bó Cúailnge to see if there can be found evidence to date the stories to the Iron Age, Early Middle Ages or High Middle Ages. The natural features of the landscape didn’t change much during these centuries so investigating the natural surroundings that are mentioned in the scéla is of little help. The built environment however, has potential. When looking at the numerous forts mentioned in the Táin and comparing this to the archaeological record, it seems more probable that this element in the scéla stems from the Early Middle Ages rather than from the Iron Age. The same is true for the warfare and weaponry described in the Táin. Heroes frequently behead their opponents, with the archaeologically proven small prehistoric and early medieval Irish swords that action would be a difficult business. This ritual behaviour could be carried out much easier and swifter with the large and heavy Viking swords introduced in Ireland around AD 800. It is probable the scribes who wrote the tales down had these kinds of swords in mind when writing about the heroic slaughterings in the Táin. We also know that beheadings took place well into the Medieval period in Ireland, and also much more frequent than they were carried out in the Iron Age.

Besides the natural and built environment and weaponry and warfare, the author also treats means of transport, most notably the chariot, burial rituals and remaing aspects of material culture in his search for evidence of this misty early period in Irish history. Mallory appropriately coined the term Irish Dreamtime for this period, which can be seen almost like a state of vague collective remembrance. The author ends his quest concluding that the earliest material culture in weaponry that can be found in the tales might date back to the Iron Age, most notably the ‘colg’, a prehistoric thrusting sword, although by the time the tales were written down, this use was forgotten and the word was used interchangeably with ‘claideb’, which indicated a slashing sword. Most of the other aspects in the tales point to an Early Medieval date or even later. Mallory explains that

“If we return to the subject of historicity, we should realize by now that while we might argue that medieval scribes may have believed that they were recording history, it is probably fairer to say that at very best they imagined they were writing stories ‘based on actual events’." (p.289)

Most of the features that we find in the tales date from the period of the scribes themselves, in order to relate to the known world of their public, the kings and people in their midst. It speaks for their remarkable imaginative writing that centuries of scholars have spent their years arguing if this world created by the medieval scribes was a genuine document of Ireland’s prehistoric past. Mallory himself did a great job too with this extraordinary piece of research, which is as accessible as it is erudite. Surely a must-read for anyone who is interested in Ireland’s early history and mythological culture!

Wouter van Dijk