Reviewer: Wouter van Dijk

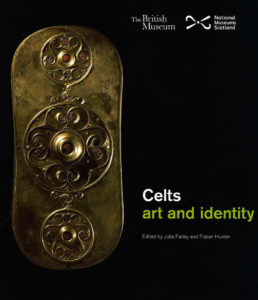

Celts. Art and identity, Julia Farley & Fraser Hunter (eds.)

British Museum & National Museums Scotland, London & Edinburgh 2015

ISBN 978 0 7141 2836 8

Paperback, lavishly illustrated, with List of Exhibited Objects, Notes, Bibliography and Index

288 pages

£ 25,00 / € 30,64

The Celts and their heritage

Today the ancient Celts continue to fascinate thousands of people all over the world, even though roughly two thousand years have passed since they vanished from our written records. However, not only the Celts of the Iron Age may rejoice themselves in a continuing interest from both scholar and layman. One of the reasons practically everyone has an idea, be it vague or precise, what you mean when you mention ‘Celtic art’ is because of the evolution of Celtic symbolism and design and its ongoing use by generation after generation of artists and craftsmen long after every trace of the Iron Age people themselves had disappeared.

The most famous branch on this tree is of course the Irish art, and book illumination, of the early Middle Ages. Celtic design continued to inspire in the centuries thereafter however, experiencing a revival in the nineteenth century and surviving into the present. The British Museum in London and the National Museum in Edinburgh, as national treasure keepers in two countries with a lively Celtic heritage, have joined forces with the presentation of a huge and wonderful exhibition about the Celts and their influence throughout the centuries.

The exhibition as well as the book that accompanies it focus primarily on language and art as two aspects of Celtic culture that definitively can be seen as distinct from surrounding cultures in Europe in the period from ca. 500 BC until 0 AD. The time span in the whole book runs from the fifth century BC until the twentieth century AD, incorporating the influence of the Romans in Britain on the art style in the isles, the medieval style mostly known from Ireland and the rediscovery of a Celtic past in the early modern period, leading to a revival of everything considered ‘Celtic’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Throughout the book the authors seize every opportunity to stress how very problematic the term ‘Celts’ in itself is. Although, and just because, it is used in a wide range of contexts, what exactly ‘Celtic’ does means often remains vague. Farley and Hunter state that there are in fact very many problems when trying to label archaeological remains as Celtic. Evidence that people adopted art styles we now label as Celtic is not enough for the authors to label them as Celts for example. Therefore they prefer to speak of Iron Age people, and stress the similarities between Iron Age cultures throughout Europe in the centuries before the Roman domination. There sure is truth in the statement that ‘Celtic’ is a problematic term, definitively to collect all people of Iron Age Europe under it, but the answer of the authors, which comes down to speak of very many different peoples throughout Iron Age Europe that shared many similarities, formerly known as Celtic, but can’t called Celtic anymore, is surely not the answer. One of the peculiarities of this new revisionist approach, although it does also has its merits, is that the Hallstatt culture (roughly 8th-6th centuries BC) is barely mentioned, although formerly seen as a precursor of, and related to, the later La Tène-art which the authors do term as Celtic. The authors take a different approach, as they do as well in the case of the Celtic language which section makes for interesting reading.

The traditionalist vision on the distribution of Celtic culture is that it spread from its birthplace in central Europe across the continent. Language research may provide us with an alternative vision. The Celtic languages seem to have developed on the fringes of Western Europe, and perhaps spread through Europe as a language of trade.

Then, another new perspective on Celtic habits; the cult of the head. The authors dismiss the so-called cult of the head among the Celts, instead they argue that there was nothing Celtic about the prominence of heads in thought and religion compared to other contemporary peoples. This may be true, but it doesn’t deny the prominent place the head, severed from an enemy’s body or worshipped from an ancestor, had in Celtic society. In their eagerness to bring forward a new revisionist image of how the Celts ought to be seen, the authors seem to have been a bit too eager to get rid of the terminology of ‘the cult of the head’, only to replace it with ‘a cult of the head’.

It is a pity society, political system and religion of the Iron Age Celts are barely treated throughout the book due to the focus on art, and to a lesser extent language. This focus however, is understandable since the book supports a museum exhibition, after all. The book is different from other books on the Celts in that it very accurately shows the development of Celtic art styles and how they were incorporated by later people and melted together with styles from other cultures such as the Roman and Anglo-Saxon art in the years 0-500 AD. After explaining how the Celtic style changed due to Roman influence, the authors devote a chapter to the comparison of Celtic art and its Anglo-Saxon counterpart in the centuries after Rome’s departure from the British Isles. Where the art objects of the Celtic-speaking population of northern and western Britain, and Ireland, was often made of silver and decorated with curvilinear swirls and spirals, Anglo-Saxon art in the east and south of Britain was characterized by the use of gold and interlaced designs, in which animals figured prominently. Today, this interlace and stylized animal figures are often seen as typically Celtic, which they are not, the authors assure us once again. Besides the treatment of the Irish art of the Middle Ages, the book also examines the Celtic Revival in Britain and Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth century, and also marks the differences as in Scotland the revival was mainly a cultural phenomenon, in Ireland it took a political turn in the beginning of the twentieth century as the revival of Irish culture and language melted together with the strive for political independence from Great Britain. This incorporation of the evolution of Celtic art beyond the Middle Ages until more or less the present day gives this book absolutely an added value compared to other books on Celtic art. Add to that the marvellous countless illustrations and you have an amazing book on the Celts, their art and their heritage. Highly recommended, and go see the exhibition if you have the chance!

Wouter van Dijk

The exhibition Celts. Art and identity can still be visited until 25 September 2016 in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Pingback:

The Celtic Myths, Miranda Aldhouse-Green |

Pingback:

The Celts, Alice Roberts |