Reviewer: Wouter van Dijk

Reviewer: Wouter van Dijk

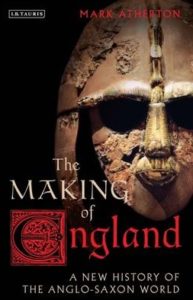

The Making of England: A New History of the Anglo-Saxon World, Mark Atherton

I.B. Tauris Publishers, London 2017

ISBN: 9781784530051

Hardcover with dust jacket, with illustrations in black-and-white, maps, appendices, notes, select bibliography and index

304 pages

£ 69,00 / € 70,98

English nation-building from Alfred to Edgar

The Anglo-Saxons have left an enduring footprint on Britain’s soil. After all they are the ones that left their language as the dominant one on the island, displacing the British tongue to the inhospitable corners of the land. It was also under a Saxon king, Alfred (849-899), that we first become aware of a more or less united kingdom on British soil that was later called Englalonde, the land of the English. Alfred, living at the end of the ninth century, was still only king of the West Saxons and of Wessex at the beginning of his reign, later expanding his rule over the Mercians when he acquired the overlordship over the former kingdom of Mercia. From then on Alfred was king of the Anglo-Saxons. In the second quarter of the tenth century, it was king Æthelstan (894-939) who first styled himself rex anglorum, king of the English, after he captured the Viking stronghold York. During the period in between, the Anglo-Saxons experienced a process of nation-building and identity-forging, which is the subject of Mark Atherton’s book.

In The Making of England Mark Atherton tells the story of the unification of the kingdoms that became England. The author is Senior College Lecturer in English Language and Literature in Regent’s Park College, Oxford. At the moment he is also Visiting Professor in English Medieval Literature at the Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf. The period under scrutiny in the book is the long tenth century, starting with the reign of Alfred the Great who stopped the Danish advance in the 870’s and ending with the kingship of Edgar the Peaceable (c.943-975) in which England as a political entity was consolidated. While covering the period Atherton devotes much attention to developments that had an influence on the nation-building process of the new state, such as the Christian religion and the use of Old English as an all-purpose language for both clerical and vernacular literature. That the role of literature features prominent in Atherton’s narrative may come as no surprise, since Atherton’s specialty is medieval literature.

The book is divided into five more or less chronological parts, each with a relevant timeline and contemporary text fragment, to be also useful if one only reads a section of the book when looking for more information about a particular event treated in the publication. Above all, it is a political and literary history, as the author explains himself in his introduction. Political in that it follows the shaping of a united England, and literary because it traces the important role of literary developments in the forming and coming to fruition of the concept of an English nation. Literature was an important factor in early medieval nation-building. At the same time Atherton stresses the importance of the use of human memory. In medieval society with its scarcity of writing materials and written works, the art of memorizing was highly developed, something we can easily overlook nowadays.

The author investigates the Old English translations of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, Orosius’s History against the Pagans and Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy in order to extract the ideas of proto-nationalism and identity-forging that they contain. However, not only translations are reviewed, but also original Old English poems such as The Battle of Brunanburgh and The Capture of the Five Boroughs. Besides the literary component, the role of the Church in the wording of the English nation is examined. Doings of bishops Dunstan (909-988) and Æthelwold (904/909-984), his former student, feature prominently herein. They were both instrumental in the continuation and progression of the study of Latin, Old English and the arts in tenth-century England. Dunstan founded a thriving school in Glastonbury under king Edgar before his fall from favour. Æthelwold on his turn, started a successful school in Winchester.

The focus on non-military developments in the violent ninth and tenth century that Atherton presents works refreshing. Of course warfare and violence were endemic in these times, but Atherton shows how intellectual enterprises were just as, and perhaps even more important to the process of uniting the ‘English people’. Therefore his book is a very valuable asset to historiography of Anglo-Saxon England.

Wouter van Dijk