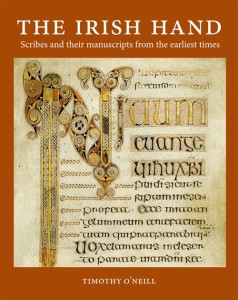

The Irish Hand. Scribes and their manuscripts from the earliest times, Timothy O'Neill

Cork University Press, Cork 2014

ISBN: 978-1-78205-092-6

Hardcover with dust jacket, lavishly illustrated in colour, with select bibliograhpy and index

136 pages

€39,00

Irish scribes and manuscripts

This book is a reworking of an earlier edition published years ago but has now been revised and expanded to celebrate more than 1500 years of Irish scribes and manuscript-making. The author, Timothy O'Neill, is a leading authority on Irish manuscripts and their history. His book is divided into two parts; in the first O’Neill presents thirty of the most famous Irish manuscripts, along with their history and some of the context in which they were produced. In the second part of the book the author elaborates further on the actual writing of the scriptures, indicating the peculiarities of every hand.

However, before taking the reader on a tour across the most marvellous manuscripts Irish history has produced, O’Neill gives an introduction into the practice of Early Medieval manuscript-making. In doing so, he reveals some details that were distinctly Irish, as opposed to the practice in continental Europe. Books in Irish monasteries were not kept in chests or cupboards as elsewhere in Europe, but hung in satchels on wooden pegs on the wall, as was done in for instance Ethiopia until modern times.

Dealing with the nature of the, mostly religious, manuscripts, O’Neill explains that the liturgical manuscripts had more meaning for the people than being just Christian religious writings. They were considered to have magical and healing properties. The 7th-century Book of Durrow was called upon to cure sick cattle and water was poured on it to release its healing powers. Another example is the ‘Cathach’ or ‘Battler’, this psalter book functioned as a battle ‘talisman’ that had to help secure victory in battle. The manuscript section of O’Neills book starts with it, and it is probably the oldest surviving Irish manuscript ni the world, dating from the 6th century. The famous Book of Durrow and Adomnán's Life of Columba are next. Despite the small amount of fully illuminated pages in the gospel book of Durrow, 11 out of a total 496 pages, the decorations that are made are of a stunning beauty. While reading about the Life of Columba by Adomnán one is grateful that the manuscript has survived its journey from Iona via France to Switzerland.

Also noteworthy are the 8th-century Book of Dimma and Book of Mulling. These are both pocket-size gospel books, intended for personal use by their owner. the church man could take his book with him on his travels, and both books are personalized by the later adding of notes, psalms and prayers. Besides the many religious texts such as hagiographies and gospels The Irish Hand also contains a lot of manuscripts of particular interest to historians; the many annals that are preserved from the Early Middle Ages. The Annals of Innisfallen are the oldest of these texts, dating from the 12th century but going back as far as the 5th century.

The Liber Hymnorum, another manuscript treated by O'Neill, is important because of its hymns written in Irish, thereby showing the use of the vernacular language in the Irish Church in the Early Middle Ages, an uncommon feature. Also some words in this review have to be dedicated to Lebor na hUidre, or the Book of the Dun Cow, named after a legendary cow skin that guaranteed a direct passage to heaven for those who died on it and which was kept in store together with the book. Later the skin got missing but the book kept its name. Lebor na hUidre derives its importance from the fact that it is the earliest manuscript known written entirely in Irish. It also contains a wealth of literary and historical source material. Created probably somewhere in the eleventh century, the book contains tales from the saga around Cú Chulainn, ancient tales such as the voyage of Máel Dúin (later used as an inspiration for the Christian Voyage of St. Brendan) and the earliest version of Táin Bó Cúailnge which is the oldest vernacular epic in Europe.

Every manuscript O’Neill examines has its own story to tell, and it would lead too far to mention them all here. However, they surely would deserve the attention. In the second part of the book, O’Neill examines a few lines from many of the manuscripts treated in Part One, and even gives some examples of modern-day scribes that continue the tradition. Himself being one of them. The combination of the large and beautiful images of the manuscripts under scrutiny, the concise history and context given by each title and the examination of the actual writing in the manuscripts makes O’Neills book a must-have for all with a love for medieval manuscripts and those interested in palaeography. Praise for The Irish Hand!

Wouter van Dijk